Download a free copy of the catalog here:

May Contain Explicit Imagery by Tucker Neel

Posted in Catalog Essay, CB1, Curate, Exhibition

May Contain Explicit Imagery

Curated by Tucker Neel

July 27 – September 7, 2014

Artists Reception: Sunday, July 27, 2014, 5 – 7 p.m.

Roundtable Discussion: Sunday, August 24, 2014, 5 – 7 p.m.

Catalog essay by exhibition curator Tucker Neel

Los Angeles Times review by Christopher Knight

CB1 Gallery presents May Contain Explicit Imagery, an exhibition exploring libidinal subjectivity, the way we project our own sexually-charged impulses onto non-figural abstraction. This exhibition unites three very different artists: Nancy Baker Cahill, Kiki Seror, and John Weston, whose disparate practices and methodologies, all create content activated through corporeal allusion. In front of each of these artists’ works the act of looking becomes self-reflectively conspicuous, as one is made aware of an unavoidable impetus to see things that are simply not there. Like Rorschach tests (but much more engaging), each of these artists’ works allows viewers the opportunity to investigate the impulses behind images that resist and also demand meaning. As the title of this exhibition implies, the images contained in the works on display, congealed in the viewer’s consciousness range from erotic to disturbing, but in the end purposefully resist “literal” interpretation.

May Contain Explicit Imagery opens on July 27, 2014 and will be on view through September 7, with a reception for the artist on Sunday, July 27, 5 – 7 p.m. A roundtable with the artists will occur on Sunday, August 24, from 5-7 p.m.

Nancy Baker Cahill’s massive graphite drawings fascinate and overwhelm viewers with evocative references to human skin, muscles, organs, and strange, unexplainable growths. The impressive body of work in this exhibition began from a series of daily sketches the artist began in 2013. Completed as a daily meditation, these small drawings are filled with forms resembling hair, mounds of flesh, and folds of human effluvia. After compiling a month’s worth of these images, Cahill noticed pains in her stomach. Scans revealed a football-sized benign tumor growing inside her stomach. After surgery and months of recovery, she embarked on Virgil, the series of intuitive and sensual large-scale drawings in this exhibition. The visceral reactions one has to Cahill’s work emphasize the powerful self-alienation we all have with our own bodies and our inability to fully comprehend the mysterious, hidden inner-mechanics and landscape of our physical existence.

KIKI SEROR, Vertigo Draws The Spirit Which It Grips; To Become One Flesh With The Crowd., 2014,

477 C-Prints, each 4″ x 6″ – installation – variable dimensions

Kiki Seror’s newest series of photographs, Let Us Leave Pretty Women To Men With No Imagination; Remembrance Of Things Past, continues the artist’s ongoing inquiry into how content, pleasure, and identity are constructed through pornographic media. For this exhibition Seror made hundreds of carefully calculated time-lapse photos of famous porno movies from the late 1970s and early 1980s, arranging them sequentially to form a spectral archive of each film. Capturing such greats as Taxi Girl and Debbie Does Dallas, Seror highlights pornography when the medium was in a transition from film to VHS, before the Internet and the death of the porno theater diminished porn’s communal, social, and cinematic potential. Seror’s gridded, mathematical, almost pedagogical display system allows viewers to consider the role context, framing, and scopophilia play in the production of subjective sexual interpretation.

JOHN WESTON, Pins and Needles, 2013, acrylic on canvas, 48″ x 36″

Standing in front of John Weston’s work guarantees an ecstatic and often hallucinatory experience. The artist has for many years been fascinated with the historical and physiological use of patterns and tessellations as a way to create meaning and activate space. Weston’s paintings lure viewers in with dazzling colors and extremely meticulous applications of paint. This ordered environment contrasts with the artist’s centralized forms, which often allude to, yet never fully render, human (and perhaps alien) states of uncontrolled disembodiment. Weston embraces the power of suggestive imagery, using negative space, and contrasting surface texture to suggest normally hidden human body parts, pulsating orifices, orgasms, ejaculations, and erogenous insides exploding with electric energy. The works in this exhibition from Weston’s Fair Is Foul and Foul Is Fairseries use the power of suggestion as a means to investigate the carnal thoughts that always lurk behind the banal. His chromatically high-key, high-contrast applications of paint result in funny and evocative compositions that, through careful titles, interrogate the sexualized implications of everyday phrases like Lip Service and Finger On The Pulse. Weston’s work purposefully activates a highly visual experience in the viewer, producing a particular representation of jouissance that radiates from the cornea throughout the entire body. This experience may make you blush, but it’s a pleasurable charge that’s hard to shake.

Posted in Cruate, Exhibition, Press Release

Kiki Seror

Hysteris

CB1 Gallery

Pornographic tastes are often some of the most telling things about a person. But porn isn’t a media that begs much self-reflection from its audience; the tantalizing pictures are too busy doing their job to worry about you. Thankfully, art and psychoanalysis often does this job for and with us. Using the power of both, the artist Kiki Seror’s recent exhibition Hysteris, takes the digital porn universe as a starting point to turn our gaze and our thoughts inward, while at the same time examining larger social phenomena wrapped up in complex online and real life sexual subjects.

Seror’s videos in this exhibition call attention to how we imagine our libidinal selves through the bodies of others. For these works Seror paints parts of her body in a saturated color and then uses real-time digital video software to color-key out parts of her body, replacing these sections with the real-time video feed of her “partner” on Chatroulette, a site that allows people to randomly video chat with others. In the videos, we see Seror using this self-erasure to throw back her Chatroulette friend’s gaze. Streams of men see their bodies where hers should be. Some are into the strange performance; they sit erect, fascinated by Seror’s ability to superimpose her floating eye, mouth, and remaining body parts on theirs. Other guys are un-amused and leave the chat, perhaps aware they are being recorded. With this work Seror deploys a kind of digital camouflage to subvert her partner’s – and the viewer’s – expectations of where a body begins and ends.

Seror complements these videos with a series of still photographs of pornographic GIFs, looping short videos made specifically for quick viewing on the Web. Seror takes her photos directly off the computer screen using long shutter speeds to blur movement. The most striking images, like Face of a Virus /gif/ifeelmyself/08, which shows a mass of interlocking flesh-like limbs and faces writhing on a bed, confuse just enough visual information to demand the viewer complete the picture. In this way, Seror’s photographs function like Rorschach tests, making one reflect on the reading of the image itself.

It’s difficult to discuss Seror’s work without acknowledging the famous German photographer Thomas Ruff, whose own photos of porn at first glance bear a striking similarity to the photos in Hysteris. Though they have similar subject matter, Ruff and Seror speak to different concerns. Ruff’s big, sofa-size photos capture a pornographic scene as if it were in-between frames, resulting in a double image. His photographs seem to be more about porn as an artifact of visual culture and in the stale white cube of the gallery they create a neutered engagement with the erotic body, the spectacle of objectification with little carnal pay off. Now some of Seror’s works participate in a similar process, duplicating porn’s aesthetic appeal while negating its function. This happens in images where the viewer can easily discern all elements in the scene, like in Face of a Virus /gif/interns/01, where two women fellate an erect penis. But thankfully in many of Seror’s other photographs the indistinct gesticulating body, made possible by an open lens (a stand-in for the voracious human eye) does something Ruff’s photographs don’t: they become other and challenge the Real, creating room for generative contemplation about bodies unmoored from prescriptive language and rigid connotation. They don’t moralize or admonish porn in a conservative sense; instead, they make you self-aware of your erotic imagination. Depending on how you feel about your own sexual appetites this can be a very rewarding process indeed.

Tucker Neel is an artist, writer, and curator in Los Angeles. He is also the director of 323 Projects, a voicemail gallery that can be reached anytime by calling (323) 843-4652.

Posted in Exhibition, Performance, photography

So, What Have You Been Up To?

Lola, Gabrielle, Katie, and Ben’s High School Reunion

By Tucker Neel

High School reunions are fascinating and kind of terrifying. These ritualized events punctuating American adulthood act as regressive time machines allowing one to return both physically and psychologically to an adolescent past. They hold the nostalgic promise of recreated memory and the elusive possibility to re-imagine what once was. At a reunion memories of the past can reveal themselves as quite unreliable because reminiscences are always fugitive, always retooling themselves to fit with an everchanging sense of self. This is why some people find themselves selectively recreating life stories or, in a Lacanian confabulation, making up outright lies when confronted wither their past. Remember Romy and Michelle saying they invented Post-its? As anyone who’s been to one knows, a reunion is often a treacherous exercise, filled with all the could-have-beens and buried hatchets unearthed and re-sharpened over too many gin and tonics. After a reunion one is left to wonder if we ever leave high school, or if we carry it with us, bearing its shape-shifting imprint forever.

Here in this gallery we have a small reunion of sorts, comprised of four Campbell Hall alumni: Lola Thompson ‘04, Gabrielle Ferrer ‘01, Katie Kline ‘01, and Ben Bigelow ‘04. Joined together by the graduation dates that will always follow their names in future school publications, these emerging artists present recent work in this newly minted gallery on a recently renovated campus. The inescapable frame of reference uniting these artists is indeed their position as subjects birthed from the very institution that houses their work-if only for the time being. One can expect this selection of artists can’t help but speak a shared language. If the works here could talk, they would probably speak of a shared productive anxiety that attends the life of an emerging artist. As you walk around in this space, imagine how the conversation unfolds. Although the works in this gallery utilize disparate media to create heterogeneous forms, they seem to me to attest to an overarching skeptical relationship to control, communication, and narrative. But remember, this is not just a reunion, it’s a testament to four devoted and emergent art practices that just happen to trace back to a common educational institution.

Many of the works in Fast Forward explore how we “read” images for underlying meaning. This is no better articulated than in Lola Thompson’s work. Thompson uses her paintings to re-imagine history or re-inscribe the present with a self-aware ridiculousness. If you’re wondering, the artist is totally in on the joke. Her paintings employ an immediately understandable form of representational illustration, often using simple outlines placed on the canvas as if traced from existing images. Painted with confident one-off brushstrokes in pure pigment colors, these images spring forth with spontaneity as if they were created minutes ago. Yet the works cannot be understood without their elaborate corresponding titles, which produce an almost didactic interplay between text and image. Titles like Walt Whitman and Leo Tolstoy demonstrate how to really bro down and Herm of Hermes Divining Locations Of Future Drone Strikes construct strange historical pairings in viewers’ minds alluding to absurd scenarios rich with contemporary urgency. In the tried and true Dada retooling of viewership, the audience “completes” Thompson’s work when they wrestle with what they see and what they are told to see. The story and image are nothing without the viewer. I would argue that this imagined and un-representable narrative in the viewer’s head is the actual subject in Thompson’s work.

Like the impossible stories in Thompson’s images, Gabrielle Ferrer’s work also references the unspeakable and unknowable space in between language and its pictorial representation. At first glance, Ferrer’s collections of bits of wire may seem inconsequential. However, these quirky lines reference symbols taken from the Lexicon of Comicana by Mort Walker, a book categorizing the symbols used in comic book illustrations to signify everything from curse words to the navigational route of a fly. Ferrer displays typologies of these line drawings referencing extrasensory information. The wire work on display also catalogs the line drawings that stand for movement around characters and the air they pass through and activate, which must be referenced in a comic strip in order to convey action, narrative, and humor. Ferrer’s curly Squeans imply intoxication. Her Swaloops indicate movement in a circular motion, like a golf swing or a spinning top. It’s no coincidence that these squeans, swaloops and spurls accompany unpleasant or out of control bodies in motion (spinning, fainting, inebriated, etc.), states one would find hard to articulate fully in words. It’s easier to convey these phenomena diagrammatically, even though as one knows, squiggly lines don’t actually appear above a drunk’s head. In literalizing these diagrams of movement and physical states, Ferrer’s work asks us to think about the limits of representation and how information is transmitted through extratextual means. Taking this into consideration these groupings read as a typology of experiences where description fails.

If Ferrer’s work touches on the inability of embodied reality to be represented with language, then Ben Bigelow’s video, The Grid, creates a similar critique of the limits of control and order. In The Grid stable objects, language, and systems of representation are always in flux. Bigelow eschews standard narrative in favor of isolated vignettes and an accumulation of scenes that always seem to portend impending discombobulation. The work, and its attendant title, point to the importance of the grid, a good ol’ staple of Cartesian rationalism allowing one to organize and observe facts against a plane of scientific order. But in Bigelow’s world this order always teeters on the precipice of destruction. The video is filled with arranged scenes that look out of control: a wildly spinning plate, a scattered mess of lined notebook paper, jumbles of numbers or unintelligible assemblies of letters. Each of these scenarios resolves itself back into a state of order and legibility, usually with the help of an omnipotent hand just off-screen, which swipes, grabs, and compresses unwieldy objects like a user would interact with a touch screen tablet. In this digital world entropy and disorder are refigured and made to behave. But in the end real control is unattainable. In one shot a pulsating burst of color gradients seems to suck in an almost indecipherable mass of letters reading, “TAKE CONTROL.” Yet the arrangement of letters and the way their rapidity and brevity deny legibility ironically implies that such a statement is impossible. Control is implied in Bigelow’s work only to be dismantled when the camera cuts away. Each scene gives way to another out of control situation, as if the process were destined to repeat itself again and again (the video is, after all, on loop).

Katie Kline’s images also evoke a distrust of narrative, resolution, and the expectations that come with representation. At first glance her images frustrate with their familiarity and surface banality. Kline’s photographs read as passing glances or frames taken in-between more dramatic shots. One finds that Kline’s photos often imply hidden action lurking just out of sight. In Spill a feathery coagulation of paint occupies the corner between a sidewalk and a stark white wall like a truncated acrylic estuary, a record of out-of-control action cut off by routine property maintenance. In Frame a pink square painted on a brick wall becomes a monochromatic backdrop awaiting a passing subject who never comes. In light of the ubiquity of picture sharing platforms like Instagram and Facebook, one might want to dismiss Kline’s work as circumstantially fortuitous, as if she were stumbling around, camera in hand. This would be a mistake. While her photographic practice does indeed implicitly reference a fascination with infinite personal documentation, a voracious way of owning the fugitive world one inhabits, Kline’s work really is about photography. Her images sit comfortably in an art historical trajectory stretching from Cartier-Bresson to William Eggleston, to Wolfgang Tillmans. Like these photographers before her, Kline proposes a surprising and engrossing way of looking for hidden treasures in daily life, using framing and light to focus attention on what might otherwise be overlooked.

Two of the artists in this show will probably return for their approaching ten-year reunion in 2014. The other two artists will have their fifteen-year reunion in 2016. In light of this exhibition, it’s worth wondering what these milestones will bring. One could easily say that any high school reunion is a leap (or a return?) into a psychic breach filled with suspect appearances, where the veracity of shared experiences and their representations are thrown into question. In this way the work in Fast Forward seems quite appropriate for what lies ahead. As the work in the gallery attests, what we see may not be what really exists and what we say may never approximate reality. Like the nervous conversations at an awkward high school reunion, our understanding of our positions in the present are always conditionally dependent on a framing and reframing of the past, which is always slipping away and changing into something else once it is remembered.

Tucker Neel is an artist, designer, curator, and writer in Los Angeles. He is also the founder and director of 323 Projects, an alternative art venue accessible 24/7 by calling (323) 843-4652.

Posted in Catalog Essay

Martin Durazo

By Tucker Neel

While discussing Jean Genet’s identification with a tube of Vaseline as a sign of the outlaw homosexual’s place in a hostile straight world, the historian and cultural critic Dick Hebdige notes, “Like Genet also, we are intrigued by the most mundane objects – a safety pin, a pointed shoe, a motor cycle – which, none the less, like the tube of Vaseline, take on a symbolic dimension, becoming a form of stigmata, tokens of a self-imposed exile”[1]. In a manner similar to Genet, Martin Durazo pays close attention to the trappings of subculture. He trades in the objects we use to signal our allegiance to, and place in the margins of society. Depending on your position within the cultural strata, an object as mundane as a handkerchief in Durazo’s work can signal working class affiliations, or extreme SM sex play – or both. A small installation of mirrors can stand for modernist design or a cocaine platter – or both. Yet with his work, Durazo always demands that viewers investigate their own place in meaning construction, actively engage in a play of semiotics, and understand how the choices we make may or may not be our own.

Yet, Durazo does not simply combine objects hoping for meaning to resolve itself. Instead, he makes informed and researched decisions in order to address complex and frustrating issues, from legal and illegal drug trades, to prisons, psychedelic substances, pornography, altered states of mind, and extreme sub-cultural affiliations. These are subjects many who see his work realize exist, but would rather not engage – at least in a “proper” public setting.

While he is no stranger to hanging isolated works on gallery walls, Durazo also constructs complex installations that look like impromptu house parties, teenage drug dens, or DIY pharmacies. Durazo’s 2010 Pain Management 100 exhibition transformed the gallery into a site for symposia, naps, raves, workshops, and the occasional drinking session. Somewhere in between, Durazo created “art”: paintings, sculptures, videos, and installations informed by these investigative interactions. The resulting conglomeration of transitory works address questions of just what kind of altered states compliment and facilitate their own appropriate environments, and vice versa. Using materials as diverse as black lights, fountains, masks, magnifying glasses, and a wealth of illicit paraphernalia, the artist charted the porous line delineating, and connecting, the legal pharmaceutical drug trade with its criminal counterpart. Through his ongoing interest in the people impacted by the drug war, Durazo poses a contemporary, yet timeless drama, highlighting the aesthetics of the modern scapegoat who, like the ancient Greek pharmakos, is cast aside into wilderness and isolation (or prison or underground economies) as a way for society to cleanse itself, maintain its own sense of righteous solidarity and cohesiveness in the face of immeasurable complexity and instability.

With his latest ongoing project, “Plata o Plomo,” Durazo continues this investigation, articulating the problematic choices one must make when inhabiting shifting positions of agency. “Plata o plomo” translates to “silver or lead,” a question posed by drug cartels demanding cooperation from legal and political figures involved in the war on drugs. This question asks one to chose between a bribe – monetary rewards from illicit and illegal drug trades, and lead – from a bullet. Durazo sometimes directly references popular images from the drug war in this recent work, whether with a transparency of a hanged victim dangling from an overpass, or copied images of traffickers worshiping Santa Muerte (the Saint of Death), or surveillance footage of famous pageant queens caught transporting drugs across the border. Though he does employ these readable signs, the artist’s work gets at his subject more tangentially, through the juxtaposition of incongruous materials and suggestive pairings.

Often, Durazo employs reflection as a device to engage the viewer and bring up questions of identity and allegiance. In one signature piece, “PLOMO,” the artist places two large mirrors atop one another, spray-painting the word “PLOMO” on protective plastic covering the bottom mirror. Like it’s fun house cousins, the top mirror bends and bows awkwardly, producing a skewed reflection of the viewer and the gallery, as if to call attention to one’s own complicity, or inspire a moment of self-acknowledgement. The bottom “PLOMO” mirror, in a state of opaque protection, registers as death and the absence of light. It’s an alarming work, eloquently summing up the artist’s engagement with the troubling subject of impossible choices, the struggle to reconcile ones self-image when confronted with Faustian choices – a bribe or a bullet, existence in service of something you don’t believe in, or nonexistence and exile into oblivion.

[1] Dick Hebdige, Subculture: The Meaning of Style, (1979; reprint, New York: Routledge, 2001), 2.

Posted in Catalog Essay

Martin Durazo’s art practice makes use of what he calls the “aesthetic of the illicit.” His work excavates the visual topography of sin, the signs of outlaw culture, the illegal and gluttonously dangerous, basically the social signifiers proper society frowns upon. Durazo has turned galleries into all night raves, made overtly libidinous videos, and fashioned installations resembling meth labs and drug nests. Throughout all of this he has dissected and re-imagined the objects and images that define the boundaries of culture, making art that continuously signals the existence of a transient bacchanalian periphery.

For this exhibition at Rio Hondo College, Durazo investigates the so-called “war on drugs,” specifically the various economies, shows of force, and acts of violence employed by Narco cartels along the US/Mexico border. The title of this exhibition, “Plata o Plomo,” takes its conceptual and historical inspiration from the question posed by these drug cartels to lawyers, judges, elected officials, and police whose job it is to stem the drug trade. “Plata o plomo” translates to “silver or lead,” metaphorically signifying a bribe for cooperation, or a bullet for resistance. While the exhibition incorporates ephemera surrounding the drug trade, like transparencies of victims of Narco violence and bombshell beauty queen traffickers, the exhibition as a whole remains much less obvious. There are no simple, prescribed ways to read the works in the gallery.

Durazo’s work doesn’t simply paint a picture of deviance, giving you a fully resolved image on which to project your own sensational desires, like so many beer commercials or porno pop-up ads. Instead, he creates complex aggregate propositions, strange and often experimental or unresolved scenarios that seem in process, like collages working themselves out. These kinds of works are perfectly articulated in the artist’s ongoing use of silver insulation sheets pockmarked with information like reflective bulletin boards, presenting disparate yet related ephemera that ask visitors to question how they create meaning. While presenting these self-reflective environments, Durazo proposes that we examine our own choices and how we label our own boundaries separating propriety from perversion, freaks from norms, straights from queers, the illegal from the legal.

Tucker Neel is an artist, writer, and curator in Los Angeles. He is also the director of 323 Projects, a telephone-based gallery that can be reached anytime by calling (323) 843-4652.

Posted in Catalog Essay, Exhibition

Tapping the Third Realm

Curated by Meg Linton and Carolyn Peter, The Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art and Design and the Laband Art Gallery at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, September 22 – December 8, 2013

Tucker Neel

Tucker Neel is an artist, writer and curator in Los Angeles. He is also the director of 323 Projects, a telephone art gallery accessible anywhere, anytime by calling (323) 843-4652. tneel@otis.edu

The first thing that strikes one when considering the exhibition, “Tapping the Third Realm,” is that the very structure of the show itself sets the stage for an experiential investigation into liminal spaces both physical and conceptual, ideological and spiritual. This liminal space is exemplified by the fact that the exhibition occurs in two separate locations: The Ben Maltz Gallery at Otis College of Art & Design and the Laband Art Gallery at Loyola Marymount University (LMU), two spaces situated in institutions that, while within walking distance from one another, span a chasm of philosophical and pedagogical belief; LMU is a Jesuit university and Otis is a very secular arts college. With the border between sacred and profane breached, this exhibition, curated by Meg Linton and Carolyn Peter, proposes to examine the in-betweens that demarcate the knowable and the unknowable, the space between life and death, art and talismanic artifact, embodiment and transcendence, and belief and skepticism. This space for artistic investigation is categorized as the “third realm,” an inspiring yet transitory place that itself resists definition. A show about spiritual experimentation might conjure expected subjects and imagery. While the show is indeed filled with spectral bodies, trippy paintings and drawings, and magic spells, the aggregate effect is more surprising and resistant to critically skeptical dismissal than one might initially suppose. In fact “Tapping The Third Realm” is a difficult and curatorially innovative exhibition, posing frustrating questions about spatial and psychic limitations. The exhibition in both spaces challenges beliefs, not just about the sacred unknown, but about the meaning and activation of art steeped in the context of such a nebulous and indefinable space.

Figs. 1-2 Above: Tapping the Third Realm (2013), installation view at the Laband Art Gallery at Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles. Below: Zach Harris, Mozart Cover Band (2006-2007), water-based paint, wood, 15 x 18 inches. Photos: Courtesy of the Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles.

As is expected in a show engaging metaphysical questions concerning the limits of consciousness and embodied existence, many works in the two galleries involve meditative practices, repetitive mark-making, explosive iridescent color choices, and the accumulation of small actions and material to form a larger whole. For example, Zach Harris’ hypnotic paintings employ undulating heavily worked abstracted landscapes that push and pull at dimensional space. Each work is held in intricate hand-made frames cutting angular lines against the gallery wall, purposefully drawing the viewer closer while also challenging the limits of the picture plane and signaling towards the potential of infinite space.

While Harris’s works are no doubt commendable for their technical dedication and conceptual explorations, one wonders about their engagement with the “third realm” articulated by this exhibition. How close do they actually get to this strange ethereal space? This frustrating question ends up extending to the exhibition as a whole. With so many works gathered together with the intended purpose of representing and/or conjuring spiritual planes of existence, is this show even able to absorb a critical reception rooted in denying artistic wishful thinking in favor of an existing discourse privileging objective visual analysis, art historical contextualization, and an acknowledgment of the limits of physical space? At first it seems that evaluating the work in this exhibition is a pointless task, akin to arguing with a believer shaking with the Holy spirit, or questioning the validity of a friend’s dream, or challenging someone who honestly believes they have just seen a ghost. Logical interpretation itself is irrational in the face of undeniably honest irrationality; the starting point for any conversation must be acceptance of the other’s immediate belief that what they experienced was in fact “real.” So where does this leave the role of the critic in this exhibition?

Fig. 3. Christopher Bucklow, Tokamak IV (2013), oil on canvas, 36 x 48 inches. Photo: Courtesy of the Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles.

In the way a blacklight poster on a dorm room wall only signals to a psychedelic experience until activated by a viewer in a psychedelic state, work about the “third realm” that speaks primarily through analogy or pictorial representation can only meet the viewer half way, by referencing a transcendent state without the embodied experience that accompanies it. For example, Christopher Bucklow’s paintings in this exhibition contain a referential interest in symbolism tied to art history, painters, and art world celebrities, but one has to take his word for how, according to the wall text accompanying his work, he creates his imagery from “studio dreams […] data from the unconscious, data from the realm of the Guest, a sort of information report from that other place.” There’s nothing wrong with this way of working; countless artists have visually tried to relay the images in their subconscious minds. But in the presence of these works one remains an outsider with little usable access to Bucklow’s third realm.

If one takes the physicality of the artworks on display and their intention to create a verifiable connection to something genuinely “unknown,” as a starting point, then at least one can ascertain that successes and failures hinge not on the accuracy of pictorial denotations (however marvelous they may be), or on how authentically the work stands as a souvenir of the artist’s experience (however earnest it may be), but on the resonance of the art object as an active producer of a metaphysical journey in the here and now, in the gallery, in the presence of the viewer, who is then made self-conscious and culpable for their logical interpretation of the truly illogical. This happens to great effect in the works of Dane Mitchell, whose simple gestures have profound resonance.

Fig. 4. Dane Mitchell, installation view of Summoning the Dead/Ancient Spell, Curse, Positive Self Reflection Spell, Warding Spell, Good Fortune Spell, Enlightenment Spell, and Cleansing Spell (all 2008), glass, spoken word. Photo: Courtesy of the Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles.

Mitchell’s contribution to the Laband gallery portion of the exhibition consists of seven oblong glass bulbs, each containing a different spell written by a pagan practitioner, spoken into the molten glass while it was blown in to expansion and then sealed forever as a fragile speech bubble. In this work one of the most popularly understood features of the third realm, a spell, is made plainly evident, framed in a beautiful but deadpan manner before the viewer. The work does not claim to be representative of the results of these pagan acts, but instead presents them as clearly as possible. The work’s greatest power is that whether one believes the spells to have their intended effect or not, one cannot doubt their presence as material in the work. In this way the artist bridges the abstract remove that so often separates viewer from mystical artifact, and instead brings the work’s audience face to face with the undeniable presence of a mystical act. Finally, Mitchell’s work demands that viewers confront their own biases and beliefs about whether or not his pieces’ engagements with third realm are indeed present and real.

Fig. 5. Annie Buckley, The People’s Tarot (Deck and Guidebook) (2013), detail of selected cards. Photo: Courtesy of the Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design, Los Angeles.

Annie Buckley’s The People’s Tarot (2013) also places the viewer in a place where they are given power to examine their own acceptance of the third realm. For her project Buckley created a tarot deck from analog and digital collage elements taken from popular media, including figures made from news article texts and contemporary pictures like the Twin Towers destruction and a laundrymat cart. She also updated the structure of the ancient fortune telling game, making it more gender neutral and less physically aggressive, doing things like replacing the suit of swords with pens. The resulting deck and accompanying instruction manual allow users to experiment in their own intuitive reading of the past, present and future. In this way Buckley gives room for viewers to go from passive observers to active participants in interpreting their own experience of their own third realms.

“Tapping The Third Realm” is a commendable and ultimately inspiring exhibition because it highlights ways of working and belief systems that are by their very nature difficult to convey and even harder to contextualize. The exhibit wrestles with its own limitations and in the end comes out having cast a spell of its own, perhaps intoxicating and entrancing one to re-examine the possibility for the presence of the unknown in daily corporeally-determined existence.

Posted in Journal Articles

Curated by Carol Ann Klonarides, Che Mondo (What A World) at the LA Municipal Art Gallery asks, “If, in the age of omnipresent digital photography, everyone can be, and in fact is, a photographer, how does one remain a ‘Photographer’”? This exhibition points to answers by presenting artists whose photographs rely on specific material execution to claim a physical presence and inscribe conceptual meaning. The result is a truly inquisitive and captivating exhibition.

One alluring body of work comes from Julie Schafer whose large pinhole camera photos document landscapes marking the borders of 19th century mining zones. These works reflect one of the most basic ways of making a photograph; light passing through a tiny aperture imprints on chemically treated paper. Printed in the negative (with light areas appearing dark and vice versa), the impressively tall photographs succeed in alienating viewers from familiar bucolic scenes like piney hilltops and desert landscapes. The work is mysterious, but perhaps too much so. Schafer’s project, which interrogates the legacies of mineral extraction and removal of indigenous peoples, could use more wall text to relay the artist’s intention. Without this the work risks coming off solely as a sign of photographic virtuosity, an updated Ansel Adams shtick.

Christopher Russell’s work convincingly merges photography and drawing to create one-of-a-kind objects. He uses an Xacto blade to scratch into the surface of a set of identical photographs, each bearing an “oops” image of a thumb on the lens. One image contains a sinking ship, another a stream of disjunctive text, and in another, frenetic lines resemble veins or brain synapses. This mark-making violates the clean surface photographers traditionally hold sacrosanct. Through this process Russell calls attention to the way we interpret photos from subjective points of view while commenting on the frailty and latent violence that comes with fixed meaning. Russell’s installation also includes a massive but conspicuously non-photographic hand-drawn artist book containing his most recent novel. However, I wish it were easier for visitors to page through the fascinating and enormous tome, which is kept safe by a Do Not Touch sign.

The most powerful work in the exhibition is Susan Silton’s Color Theory, which consists of a chair facing a projector screen, which presents a never-ending loop of images emanating from an old school projector. Sitting in a single chair, one watches a slow pan of stamps taken from the artist’s grandfather’s collection from the Third Reich, each bearing the image of Adolph Hitler. This philatelist archive invites questions about collecting the past as a way to view the present. Here Hitler’s image speaks to photography’s use in propaganda, while the stamps sign to the record of a country’s official history as well as a the currency of communication. Finally the slide projector, itself all but obsolete, engenders a didactic experience. Yet what we “learn” from this set up remains elusive. The work’s cool detachment allows for self-reflection and perhaps a bit of indictment, a moment of serious rumination on the passage of time from one fascist institution to the next.

Posted in Artpulse, photography

Alexis Smith

Slice of Life at Honor Fraser

Alexis Smith is an O.G. collage artist whose parings of text and image have unraveled complex narratives in viewers’ minds for nearly half a century. Her first show at Honor Fraser, Slice of Life, is a kind of retrospective of sorts, including work from as far back as the 1980s. The exhibition is a testament to Smith’s ongoing role as a keen observer of American culture, a continuing inspiration to generations of artists to come.

Slice of Life’s highlight is undoubtedly Past Lives, a work originating in 1989 as a collaboration with the writer Amy Gerstler. The installation takes up an entire room, filling it with a diverse collection of weathered children’s chairs, from a classic wooden rocker to a Lilliputian canvas director’s chair. As one circumnavigates the empty seats, a palpable sense of absence takes hold. Nearby, a schoolroom chalkboard bears sentences befitting an obituary headline, like, “Came to literature late.” The entire installation conjures thoughts of how indoctrination marks one from early childhood, how ideology, circumstance, and the language of control determines the roles we play in life.

Alexis Smith, Black and Blue for Howie Long, 1997. Mixed media collage, 29 x 19 x 4 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Many of Smith’s works use humor as a foil to discuss issues of violence, manipulation, and American culture. This is no better seen than in a 1997 mixed media collage, “Black and Blue for Howie Long.” In this work we read the NFL player and bit actor Howie Long’s pithy quote, “ I am an artist. My art is assaulting people” written in comic sans on a large painter’s palette alongside a photograph of two men wrestling, with one head replaced by a Georgia Bulldog’s face. Continuing the sports tableau, a baseball bat and children’s toy tomahawk sit atop the palette like menacing paintbrushes. The work’s tautological wordplay ricochets around the gallery, branding the “artist” as a contextual and perhaps menacing position. Such a proposition deserves a chuckle. Yet the play of meaning doesn’t stop there. The baseball bat and tomahawk continue the chain of signification, pointing to both America’s pastime: baseball, and America’s past time: Native American history and identity and a culture relegated to sports mascots and comic caricatures. At least that’s how I see it.

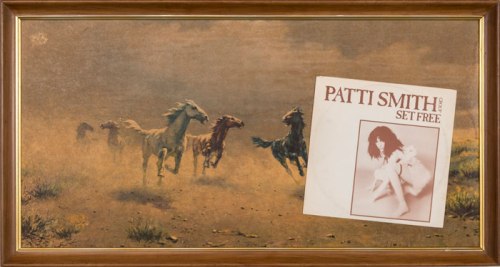

There are equally engaging recent works in the show, like “Wild Horses,” a 2012 collage of the cover of the Patti Smith Group EP “Set Free” placed above a thrift store painting of unbridled horses in a desert landscape. Such a simple construction performs impressive and lasting tricks, riffing on questions of high and low, artistic titling, and the importance of name recognition. Its word and image play is so perverse I wish it were a billboard on Sunset Blvd.

Alexis Smith, Wild Horses, 2012. Mixed media collage, 22 x 24 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Like Rauschenberg before her, Alexis Smith’s work, at its best, plays expertly on the precipice of communication. In her most successful works signifiers flirt with intelligibility while refusing didacticism. Smith’s constructs her signifiers with considered arrangement, with just enough connections to create an ouroboros of signs, with one image’s meaning devouring another, with no final cathartic “resolution.” The images turn back on themselves allowing for a slow-burn critique that always finds itself home in the present.

Tucker Neel is an artist, writer, and curator in Los Angeles. He is also the director of 323 Projects, a voicemail gallery that can be reached anytime by calling (323) 843-4652.

Posted in Artpulse, Exhibition

This press release was a work of art I contributed to Artillery Magazine’s “Celebrity” issue in July of 2013. The press release was published, as is, with no explanation, in the magazine.

DOWNLOAD THE PRESS RELEASE HERE:

FULL TEXT:

The National Museum of American History to Exhibit Artworks by Presidents Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush

The National Museum of American History is pleased to presentPresidential Pictures: Paintings & Drawings by Dwight D. Eisenhower, Ronald Reagan, and George W. Bush. This unprecedented exhibition brings together works from three of the most powerful and influential men in American history. Presidential Pictures will no doubt open the public’s eyes to the fact that these men were not just great politicians but also true artists.

While he is best known as the American president who desegregated the U.S. armed forces and public schools, signed the Civil Rights Act of 1957 and 1960, and articulated the anti-Communist “domino theory,” Dwight D. Eisenhower was also a dedicated painter. Having taken up the art in 1948 to relieve the stress of being Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, Eisenhower created hundreds of images before, during and after his presidential tenure. He even had an artist’s studio installed in the White House. Always a straight-shooter, the former President was quick to dismiss symbolic meanings viewers might read into his tranquil images of farm houses, mountains, and mirthful family members. At a 1967 exhibition of his paintings, the former president told United Press International reporter Richard Cohen, “They would have burned this [expletive] a long time ago if I weren’t the president of the United States.” Referring to his portrait of Abraham Lincoln—based on a photo by Alexander Gardner—one cannot help but consider the thoughts that went through the artist’s mind as he carefully rendered the shine on the forehead of his heroic predecessor. President Eisenhower’s work is provided courtesy of the Dwight D. Eisenhower Museum, The Lyndon Baines Johnson Library & Museum, and David and Julie Nixon Eisenhower.

It’s no secret that Ronald Reagan was an actor before he was a politician, starring in dozens of films, from Santa Fe Trail to The Voice of The Turtle. Political and film historians have proposed that President Reagan’s work as a stage and screen actor, President of The Screen Actors Guild, and spokesman for General Electric, allowed him to cultivate a “Teflon” façade, an impermeable presence that deflected criticism from the Iran-Contra affair to his indolence at the dawn of the AIDS crisis. But did you know President Reagan was also a cartoonist before and after his time in office? Visitors to this exhibition will get the rare chance to explore President Reagan’s prolific drawing practice through his images of cowboys, horses, football stars, butlers and even caricatures of hook-nosed men and mustachioed Asian faces. As President Reagan said in a 1984 letter to political cartoonist Jeff MacNelly, “I am a cartoon aficionado up to and including reading the comics every morning.” Amidst these pictures—most of them doodled on White House stationery—one sees the president’s externalized mental space in the moments between moments, when meetings got a little too boring and he needed some distraction. President Reagan’s work comes to us courtesy of The Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Library and the many private collectors credited in the exhibition’s catalog.

Unlike his artistic predecessors, George W. Bush took up the palette knife after leaving office. America knows the Decider in Chief as the man who battled for the contentious 2000 election, initiated the invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, and signed The Patriot Act into law. But in 2014, President Bush had his first museum show of portraits comprising images of global leaders such as Vladimir Putin and the Dalai Lama, all taken from the Google image search engine. Since then, he’s never looked back. Speaking of his now prolific painting practice, President Bush told CNN’s John King, “I relax. I see colors differently. I am, I guess, tapping a part of the brain that, you know, certainly never used when I was a teenager.” Amongst the former president’s numerous portraits, visitors will have the opportunity to fully experience the former Commander in Chief’s visual perspective on what it was like to connect with global leadership. President Bush’s paintings appear courtesy of The George W. Bush Presidential Library and Museum.

A catalog with essays by Lynne Cheney, Jerry Saltz and Roberta Smith accompanies this exhibition.

Special Events:

Feb. 6: To celebrate his birthday, the museum will screen Knute Rockne: All American, starring the former president. A panel moderated by former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger will follow.

Starting Feb. 14, President George W. Bush will teach a 10-week drawing and painting class, focusing on classical technique. Students will produce a portrait and a still life, using live models and nature mortes arranged specifically by the 43rd president. Reservations required.

Up Next At The Museum:

Missing! A photographic survey of looted artifacts from the Vietnam, Afghan and Iraq wars.

Posted in Politics, Public Art, Scandal, Tucker Neel's Projects